よむ、つかう、まなぶ。

慶應義塾大学 岸本特任教授 御提出資料 (2 ページ)

出典

| 公開元URL | https://www8.cao.go.jp/kisei-kaikaku/kisei/meeting/wg/2310_04medical/231218/medical04_agenda.html |

| 出典情報 | 規制改革推進会議 健康・医療・介護ワーキング・グループ(第4回 12/18)《内閣府》 |

ページ画像

ダウンロードした画像を利用する際は「出典情報」を明記してください。

低解像度画像をダウンロード

プレーンテキスト

資料テキストはコンピュータによる自動処理で生成されており、完全に資料と一致しない場合があります。

テキストをコピーしてご利用いただく際は資料と付け合わせてご確認ください。

Since psychiatric outpatient care primarily involves face-to-face

conversations, physician-to-patient telemedicine via live two-way

video is easily applicable in this field and has long been used.1 Moreover, this expanded into worldwide use with the coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. According to a survey conducted by the

World Health Organization, 70% of the 130 countries surveyed had

telemedicine in place to continue providing psychiatric and mental

health services during the pandemic.2 This increase in use may partially

be due to advances in information and communication technology that

have led many people to own smartphones and other devices. As a

result, two-way video has become a familiar means of telecommunication that can be easily and conveniently performed using these devices.

Another main reason is the deregulation that took place in many countries around the world during the pandemic period.3,4

Even before the pandemic, many studies have compared the effectiveness of two-way video and face-to-face treatment and reported that

two-way video treatment can provide comparable or better treatment

efficacy, patient satisfaction, and medication adherence.5–8 We recently

conducted a meta-analysis including 32 randomized controlled trials

(RCTs) and found that, in general, two-way video has comparable

treatment effects compared with face-to-face treatment.9 However, most

existing studies focused only on a single disorder, such as depression

or posttraumatic stress disorder, and only three RCTs looked at multiple conditions simultaneously.10–12 Furthermore, these RCTs were conducted under special conditions, such as with a dedicated line set up

between clinics and patients visiting one clinic to be seen by a psychiatrist who was physically present at another clinic.10–12 More importantly, many of these trials did not necessarily examine long-term

treatment effects. The majority of psychiatric treatment is subacute or

maintenance treatment, and the possibility that long-term treatment via

two-way video may be less effective or that the physician-patient relationship may differ from face-to-face treatment should be considered.

These validations are especially important now that smartphones and

tablets with smaller screens are being used by patients treated at home

rather than in a dedicated room with a large screen and a dedicated line

for two-way video calls.

Although Japan is a developed country with a robust health

care infrastructure, the use of two-way video is not widespread

because of regulations as well as other factors such as restrictions

on prescribing drugs used in psychiatry and reimbursement prices

being lower than those for face-to-face treatment.3,13 Behind this

strict regulation of telemedicine was the concern that it would accelerate inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepine and Z-drugs,14

which have become a problem in Japanese psychiatric care,15 and

the lack of evidence in Japan.13,16 Furthermore, although Japan has several unique circumstances, such as universal health insurance, relatively

low treatment costs, and a busy medical workforce,17–19 there is still no

evidence regarding the effectiveness, safety, and patient satisfaction of

two-way video compared with face-to-face treatment.

Therefore, the current study was designed to validate telemedicine in the new era of easy access to medical care from home, mainly

through smartphone usage. To the best of our knowledge, this was

the largest pragmatic trial that has followed the course of treatment

for 6 months or longer, targeting multiple psychiatric disorders. In

Psychiatry and

Clinical Neurosciences

particular, this was the first trial of its kind to compare two-way video

using smartphones and other devices with face-to-face treatment.

As mentioned earlier, telemedicine is not fully covered by insurance

in Japan. To promote better policy-making, it is important to conduct

pragmatic trials tailored to each country’s health care system. This trial

also plays a role in establishing evidence for telemedicine in Japan,

including areas other than psychiatry.

Methods

Study Design

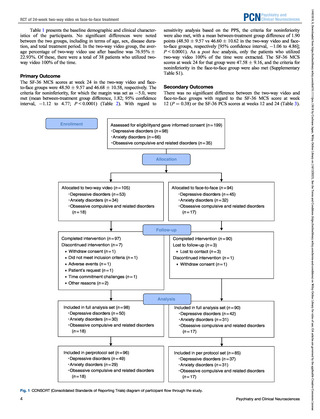

Details regarding the study methods and protocols have been previously published.20 This was a multisite, prospective RCT. Patients

were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either a two-way video group (at least

50% of treatment sessions to be conducted by two-way video, with at

least one face-to-face session within 6 months) or the face-to-face

group (all treatments sessions to be face-to-face). Patients in the twoway video group interacted with their psychiatrists from a private

location, such as their home or office, using a smartphone, tablet, or

personal computer. Both groups received standard treatment covered by

public medical insurance for 24 weeks. The intervals between treatments

were determined at the discretion of the psychiatrist in charge.

Participants

Participants were recruited at 19 medical institutions providing psychiatric services in 11 prefectures in Japan between April 2021 and

February 2022.

Patients were included based on the following inclusion criteria:

(1) met DSM-521 criteria for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders,

or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders and

were outpatients at a participating medical institution; (2) were

18 years or older at the time of obtaining consent; (3) needed continuous treatment for the next 6 months or more (at the discretion of the

attending physician); (4) had a smart phone or personal computer as

well as access to video-calling over the internet (even if available only

with family support); (5) their psychiatric condition was stable

enough for them to undergo two-way video treatment, based on the

clinical judgment of the attending physician; (6) their psychiatric condition was stable enough for them to have sufficient capacity to provide consent, based on the clinical judgment of the attending

physician; and (7) provided written consent to participate in the study.

For patients who were minors (younger than 20 years), written consent had to be obtained from the patient and his/her guardian.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) likelihood of requiring

unscheduled or urgent treatment at a hospital in addition to regular

treatment because of emergent suicidal ideation, anxiety, or agitation;

and (2) patients who would have had difficulty in managing an emergency visit by themselves if their psychiatric condition deteriorated

(e.g. the hospital was far away).

Randomization

Participating patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either

the two-way video group or the face-to-face group for treatment during the study period. To avoid interinstitutional differences and biases

19

Numazu Chuo Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan

Amagai Mental Clinic, Yokohama, Japan

Takamiya Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

22

Shioiri Mental Clinic, Yokosuka, Japan

23

Kanazawabunko Yell Clinic, Yokohama, Japan

24

Neyagawa Sanatoriumu, Osaka, Japan

* Correspondence: Email: taishiro-k@mti.biglobe.ne.jp

Primary field: Psychotherapy and psychopathology.

Secondary fields: Social psychiatry and epidemiology.

Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), 20F Yomiuri Shimbun Bldg. 1-7-1 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004 Japan.

Tel: +81-3-6870-2200, Fax: +81-3-6870-2241, Email: jimu-a sk@amed.go.jp.

†

Taishiro Kishimoto and Shotaro Kinoshita are equally contributed.

‡

Group members are listed in the Acknowledgments.

20

21

2

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences

14401819, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pcn.13618 by Cochrane Japan, Wiley Online Library on [16/12/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

PCN

RCT of 24-week two-way video vs face-to-face treatment

conversations, physician-to-patient telemedicine via live two-way

video is easily applicable in this field and has long been used.1 Moreover, this expanded into worldwide use with the coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. According to a survey conducted by the

World Health Organization, 70% of the 130 countries surveyed had

telemedicine in place to continue providing psychiatric and mental

health services during the pandemic.2 This increase in use may partially

be due to advances in information and communication technology that

have led many people to own smartphones and other devices. As a

result, two-way video has become a familiar means of telecommunication that can be easily and conveniently performed using these devices.

Another main reason is the deregulation that took place in many countries around the world during the pandemic period.3,4

Even before the pandemic, many studies have compared the effectiveness of two-way video and face-to-face treatment and reported that

two-way video treatment can provide comparable or better treatment

efficacy, patient satisfaction, and medication adherence.5–8 We recently

conducted a meta-analysis including 32 randomized controlled trials

(RCTs) and found that, in general, two-way video has comparable

treatment effects compared with face-to-face treatment.9 However, most

existing studies focused only on a single disorder, such as depression

or posttraumatic stress disorder, and only three RCTs looked at multiple conditions simultaneously.10–12 Furthermore, these RCTs were conducted under special conditions, such as with a dedicated line set up

between clinics and patients visiting one clinic to be seen by a psychiatrist who was physically present at another clinic.10–12 More importantly, many of these trials did not necessarily examine long-term

treatment effects. The majority of psychiatric treatment is subacute or

maintenance treatment, and the possibility that long-term treatment via

two-way video may be less effective or that the physician-patient relationship may differ from face-to-face treatment should be considered.

These validations are especially important now that smartphones and

tablets with smaller screens are being used by patients treated at home

rather than in a dedicated room with a large screen and a dedicated line

for two-way video calls.

Although Japan is a developed country with a robust health

care infrastructure, the use of two-way video is not widespread

because of regulations as well as other factors such as restrictions

on prescribing drugs used in psychiatry and reimbursement prices

being lower than those for face-to-face treatment.3,13 Behind this

strict regulation of telemedicine was the concern that it would accelerate inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepine and Z-drugs,14

which have become a problem in Japanese psychiatric care,15 and

the lack of evidence in Japan.13,16 Furthermore, although Japan has several unique circumstances, such as universal health insurance, relatively

low treatment costs, and a busy medical workforce,17–19 there is still no

evidence regarding the effectiveness, safety, and patient satisfaction of

two-way video compared with face-to-face treatment.

Therefore, the current study was designed to validate telemedicine in the new era of easy access to medical care from home, mainly

through smartphone usage. To the best of our knowledge, this was

the largest pragmatic trial that has followed the course of treatment

for 6 months or longer, targeting multiple psychiatric disorders. In

Psychiatry and

Clinical Neurosciences

particular, this was the first trial of its kind to compare two-way video

using smartphones and other devices with face-to-face treatment.

As mentioned earlier, telemedicine is not fully covered by insurance

in Japan. To promote better policy-making, it is important to conduct

pragmatic trials tailored to each country’s health care system. This trial

also plays a role in establishing evidence for telemedicine in Japan,

including areas other than psychiatry.

Methods

Study Design

Details regarding the study methods and protocols have been previously published.20 This was a multisite, prospective RCT. Patients

were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either a two-way video group (at least

50% of treatment sessions to be conducted by two-way video, with at

least one face-to-face session within 6 months) or the face-to-face

group (all treatments sessions to be face-to-face). Patients in the twoway video group interacted with their psychiatrists from a private

location, such as their home or office, using a smartphone, tablet, or

personal computer. Both groups received standard treatment covered by

public medical insurance for 24 weeks. The intervals between treatments

were determined at the discretion of the psychiatrist in charge.

Participants

Participants were recruited at 19 medical institutions providing psychiatric services in 11 prefectures in Japan between April 2021 and

February 2022.

Patients were included based on the following inclusion criteria:

(1) met DSM-521 criteria for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders,

or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders and

were outpatients at a participating medical institution; (2) were

18 years or older at the time of obtaining consent; (3) needed continuous treatment for the next 6 months or more (at the discretion of the

attending physician); (4) had a smart phone or personal computer as

well as access to video-calling over the internet (even if available only

with family support); (5) their psychiatric condition was stable

enough for them to undergo two-way video treatment, based on the

clinical judgment of the attending physician; (6) their psychiatric condition was stable enough for them to have sufficient capacity to provide consent, based on the clinical judgment of the attending

physician; and (7) provided written consent to participate in the study.

For patients who were minors (younger than 20 years), written consent had to be obtained from the patient and his/her guardian.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) likelihood of requiring

unscheduled or urgent treatment at a hospital in addition to regular

treatment because of emergent suicidal ideation, anxiety, or agitation;

and (2) patients who would have had difficulty in managing an emergency visit by themselves if their psychiatric condition deteriorated

(e.g. the hospital was far away).

Randomization

Participating patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either

the two-way video group or the face-to-face group for treatment during the study period. To avoid interinstitutional differences and biases

19

Numazu Chuo Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan

Amagai Mental Clinic, Yokohama, Japan

Takamiya Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

22

Shioiri Mental Clinic, Yokosuka, Japan

23

Kanazawabunko Yell Clinic, Yokohama, Japan

24

Neyagawa Sanatoriumu, Osaka, Japan

* Correspondence: Email: taishiro-k@mti.biglobe.ne.jp

Primary field: Psychotherapy and psychopathology.

Secondary fields: Social psychiatry and epidemiology.

Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), 20F Yomiuri Shimbun Bldg. 1-7-1 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004 Japan.

Tel: +81-3-6870-2200, Fax: +81-3-6870-2241, Email: jimu-a sk@amed.go.jp.

†

Taishiro Kishimoto and Shotaro Kinoshita are equally contributed.

‡

Group members are listed in the Acknowledgments.

20

21

2

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences

14401819, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pcn.13618 by Cochrane Japan, Wiley Online Library on [16/12/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

PCN

RCT of 24-week two-way video vs face-to-face treatment